Human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency sydrome

Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) causes damage to your immune system, affecting your ability to fight disease. Without treatment, some people with HIV develop the potentially life-threatening condition, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Key points

- HIV is the name of the virus that causes an infection that damages your immune system and weakens your ability to fight infection and disease.

- Left untreated, HIV can cause AIDS – the most advanced stage of HIV infection. This means that you can be infected with HIV (a virus) without having AIDS (an illness).

- A person with AIDS has a severe deficiency of their immune system, which increases their risk of severe infections.

- HIV is a sexually transmitted infection and can also be spread by sharing needles.

- While there is no cure for HIV, it can be controlled with a combination of medicines, known as antiretroviral therapy (ART). Most people living with HIV who are on ART will never develop AIDS.

How is HIV spread? (based on germ theory)

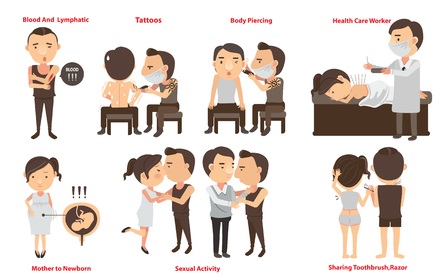

HIV is found in some of the body fluids of an infected person, such as semen, vaginal and anal fluids, blood and breast milk. It can be spread by having unprotected sex (without a condom) with an infected person or by sharing infected needles and other injecting equipment. It can also be passed on from a mother to her baby during pregnancy and delivery.

You can’t become infected through ordinary day-to-day contact such as kissing, hugging, shaking hands or from sharing personal objects, food or water.

Who is at risk of HIV?

| Behaviours and conditions that put individuals at greater risk of contracting HIV | |

| Having unprotected anal or vaginal sex.Having another sexually transmitted infection (STI) such as syphilis, herpes, chlamydia, gonorrhoea or bacterial vaginosis.Sharing contaminated needles, syringes and other injecting equipment and drug solutions when injecting drugs. | Receiving unsafe injections, blood transfusions and tissue transplantation, and medical procedures that involve unsterile cutting or piercing.Experiencing accidental needle-stick injuries, a risk particularly for healthcare workers. |

What are the stages of HIV?

When people get HIV and don’t receive treatment, they usually progress through 3 stages of disease.

- Stage 1 – acute HIV infection

- Stage 2 – clinical latency (HIV inactivity or dormancy)

- Stage 3 – acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Medicine to treat HIV, known as antiretroviral therapy (ART), helps people at all stages of the disease if taken as prescribed. Treatment can slow or prevent progression from one stage to the next.

People with HIV who take HIV medicine as prescribed and get and keep an undetectable viral load have effectively no risk of transmitting HIV to an HIV-negative partner through sex. Read more about the stages of HIV infection.

How do I know if I have HIV?

The only way to know for sure whether you have HIV is to get tested. Knowing your status is important because it helps you make healthy decisions to prevent getting or transmitting HIV. If HIV infection is found in your blood, you are said to be HIV positive.

How often you should get tested (the frequency of testing) depends on who you have sex with and what type of sex you have. Use the ‘Testing frequency calculator‘ (NZ AIDS Foundation) to get a recommendation on how often you should be tested.

If you think you may have been exposed to HIV, you can use the ‘Been exposed tool‘ (NZ AIDS Foundation) to find out the likely risk of a specific event or encounter. If you were at risk of HIV exposure you will also get a recommendation for next steps.

- If you think you may have been exposed to HIV, your doctor, Family Planning clinic, sexual health clinic or the New Zealand AIDS Foundation can arrange a blood test. The result is confidential.

- If your first test suggests you have HIV, a further blood test will needed to confirm the result.

- If this is positive, you’ll be referred to a specialist HIV clinic for some more tests and a discussion about your treatment options.

- There is a short period just after being infected with HIV when the virus cannot be detected. If you have been exposed to HIV, you may need a follow-up test 3 months later.

- Note: HIV is a notifiable disease which means that it is a legal responsibility for your healthcare provider to notify public health authorities of a HIV positive result. In the notification, you will not identified by name or address (it is anonymous).

How is HIV treated?

While there is no cure for HIV, it can be controlled with a combination of medicines, known as antiretroviral therapy (ART). These work by stopping the virus replicating (spreading) in your body, allowing your immune system to repair itself and preventing further damage. Taking these medicines can reduce the amount of virus in your body and help you stay healthy, and can also help prevent you passing the virus on to others.

You will also be encouraged to have regular exercise, eat a healthy diet, stop smoking and have the flu vaccine every year to lessen the risk of getting serious illnesses. Without treatment, your immune system will become severely damaged and life-threatening illnesses such as cancer and severe infections can occur. Read more about antiretroviral therapy.

How can I prevent HIV infection?

There are a few things you can do to protect yourself from HIV.

- Practice safe sex: Using condoms and water-based lubricant correctly every time you have vaginal or anal sex reduces the risk of getting HIV by around 95%. In New Zealand, HIV is most commonly caught by having unprotected sex with an infected person.

- Don’t share needles: If you inject yourself with drugs, it’s important to use new needles and syringes. Blood is left on syringes and needles every time they’re used. If you share injecting equipment, you can catch HIV from another person’s blood if they are infected.

- Have HIV antenatal screening: Women with HIV can pass it on to their babies during pregnancy, birth and while breastfeeding. If you’re pregnant, you’ll be offered a screening test for HIV at the same time as you have your other blood tests, as a routine part of your antenatal care. The screening programme is run by the National Screening Unit. If you’re found to have HIV, you’ll be offered treatment that reduces the chance of your baby becoming infected from about 25% to less than 2%.

- Use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): This is an HIV prevention method for people who do not have HIV but who are at risk. By taking a pill every day you can reduce your risk of becoming infected with HIV. Read more about PrEP.

- Use post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP): This is an emergency medication for people who do not have HIV but are likely to have been exposed to the disease (eg, from a needle-stick injury or sexual assault).

If you are HIV positive, you can take precautions to avoid spreading the infection to others.

- Take your antivirals. It can suppress your viral load to being undetectable and there is almost no risk of sexual transmission if your viral load stays undetectable.

- Tell your sex partner or partners about your relevant behaviour and whether you are HIV-positive. Read more about partner notification.

- Follow safer sex practices, such as using condoms. Read more about safer sex 101 for HIV.

- Don’t donate blood, plasma, semen, body organs or body tissues.

- Don’t share personal items, such as toothbrushes, razors or sex toys, that may be contaminated with blood, semen or vaginal fluids.

Learn more

All about testing NZ AIDS Foundation

Partner notification and contact tracing NZSHS

Living well with HIV NZ AIDS Foundation

NZ AIDS Foundation Information and support

HIV/AIDS Ministry of Health, NZ

HIV Healthy Sex, NZ

Body Positive NZ

References

- HIV basics Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- General practitioners and HIV Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine (ASHM), 2020

Reviewed by

| Dr Li-Wern Yim is a travel doctor with a background in general practice. She studied medicine at the University of Otago, and has a postgraduate diploma in travel medicine (Otago). She also studied tropical medicine in Uganda and Tanzania, and holds a diploma from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. She currently works in clinical travel medicine in Auckland. |

Image credit: Canva

Image credit: Canva Image credit: Te Whatu Ora

Image credit: Te Whatu Ora

Phone

Phone